Simultaneous grouping (Figure 6)

Click the cochleagrams in the figures to hear the corresponding sound.

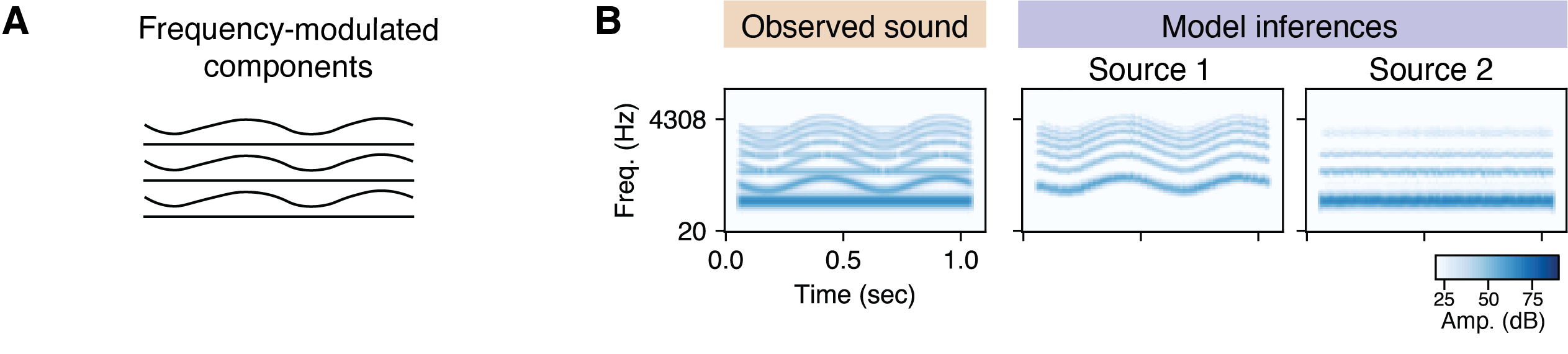

Frequency modulation (McAdams, 1984)

Modulating the frequency of a subset of tonal components in parallel also causes them to perceptually separate from an otherwise harmonic tone. Click the figure above to hear the experimental stimuli and the model inferences.

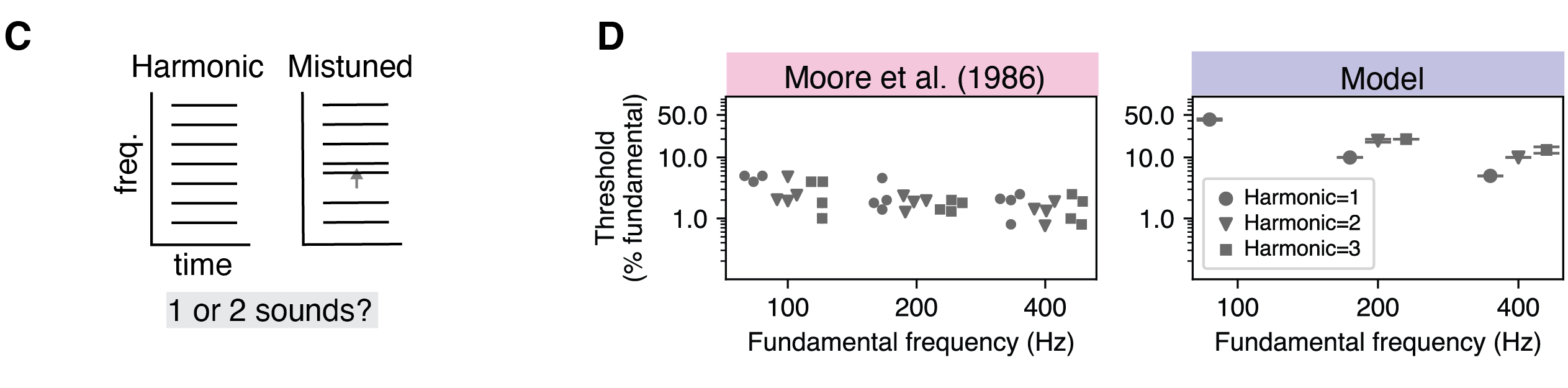

Mistuned harmonic (Moore, Glasberg, and Peters, 1986)

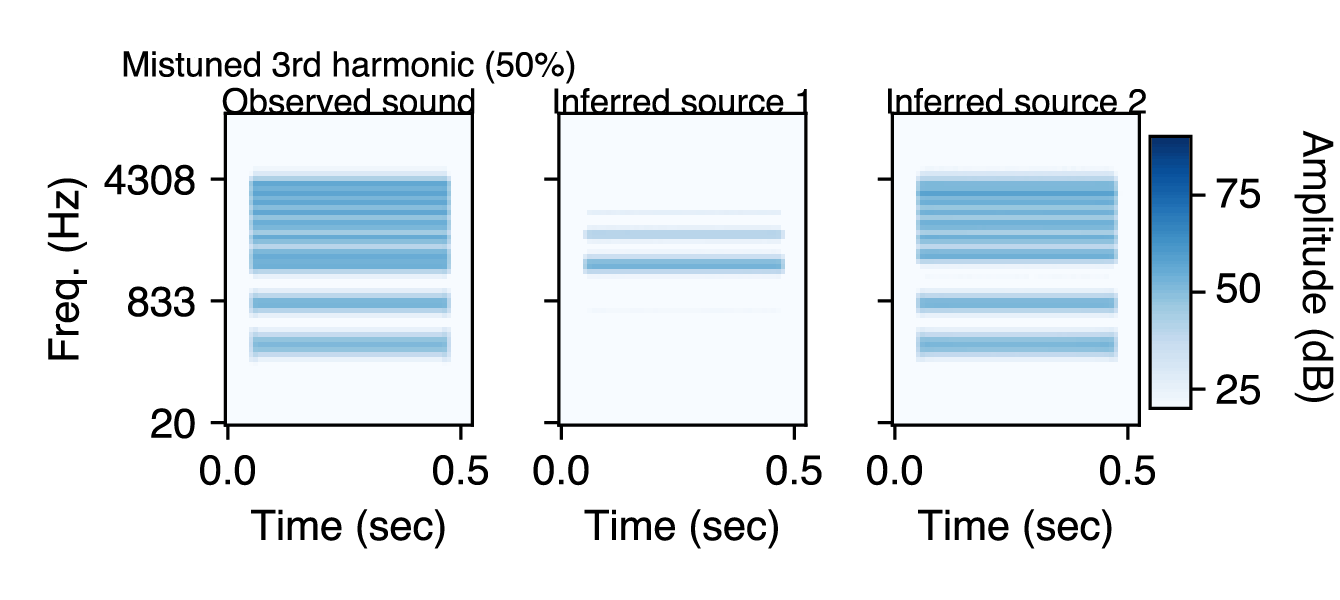

Listeners tend to hear tonal components with harmonically related frequencies as a single perceptual entity. When the frequency of one tonal component deviates from the harmonic series, the component is heard to stand out as a separate tone.

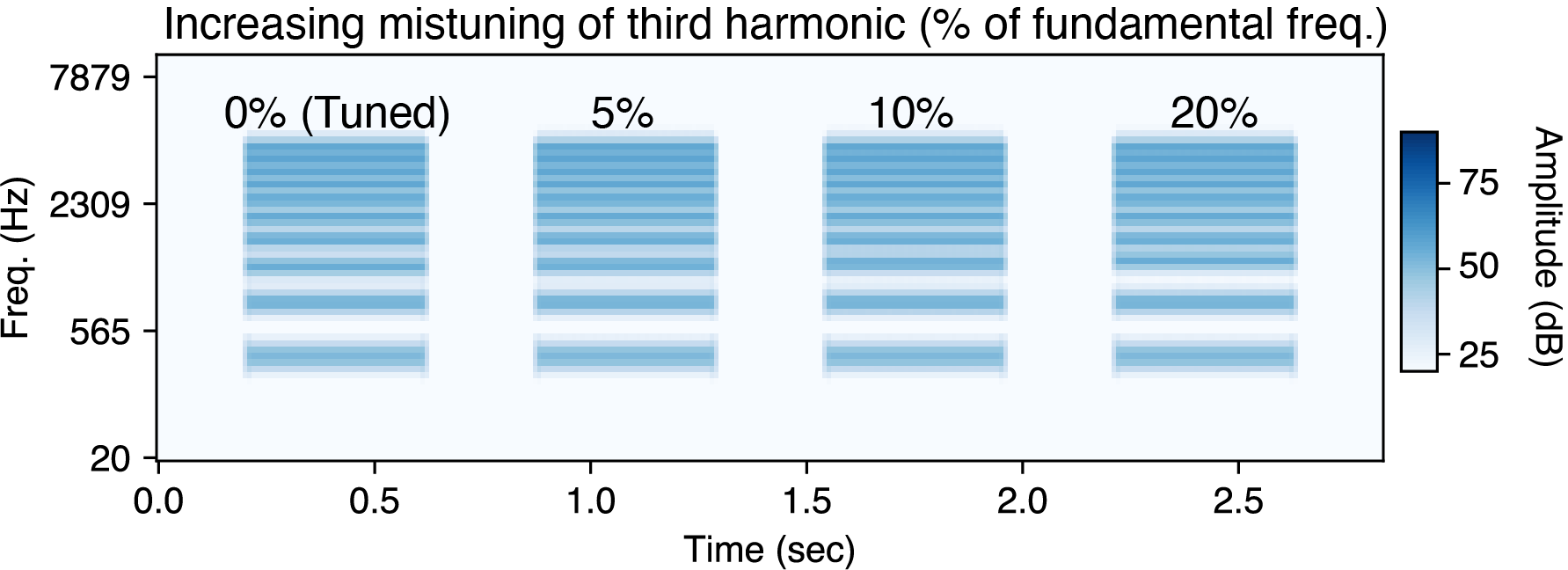

Here are example experimental stimuli with increasing degrees of mistuning. The first tone is tuned so you should hear a single sound. For the subsequent tones, you can hear a complex and a pure tone.

Finally, the following is a model inference (using sequential inference).

Asynchronous onsets (Darwin and Sutherland, 1984)

What is perceived when components are harmonically related but start and end at different times? This situation can be considered a "cue conflict", with harmonicity favouring grouping and asynchrony favouring segregation.

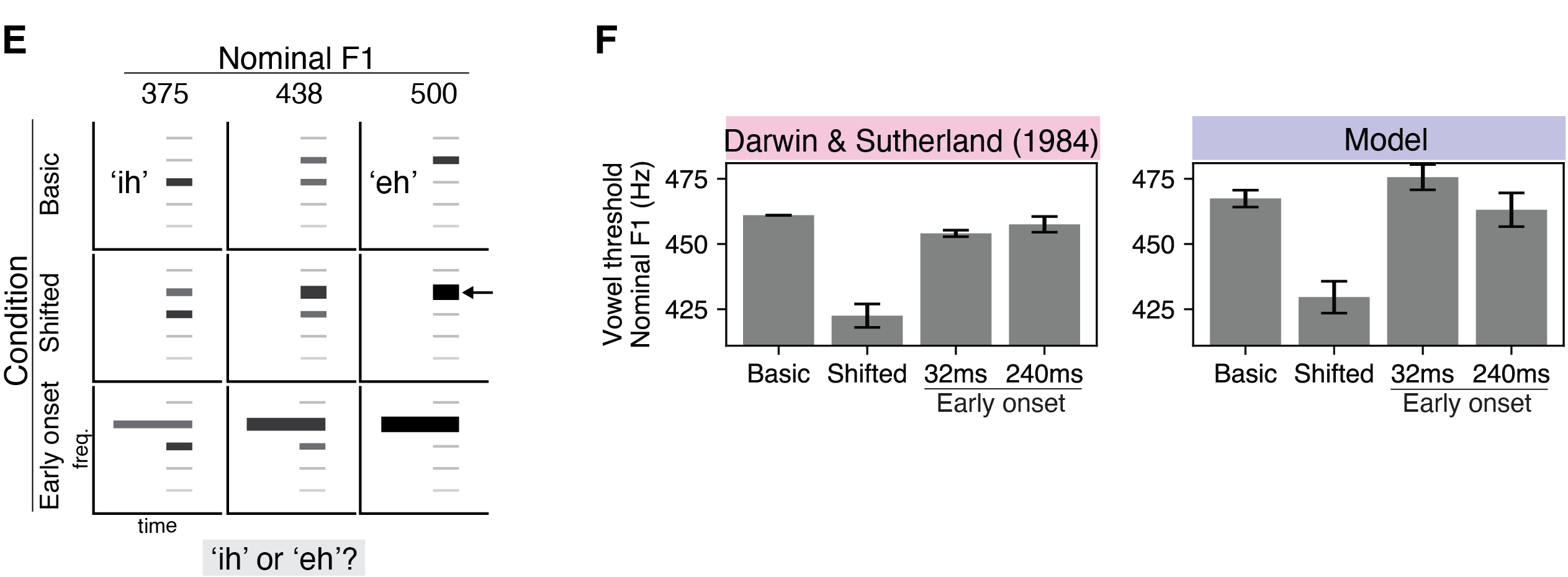

Darwin and Sutherland (1984) examined the case where the components are harmonic but do not share a common onset. To determine whether a component of a harmonic sound was perceptually grouped with the others, they used judgments of vowel quality (in particular, whether a sound was perceived as /I/ or /e/).

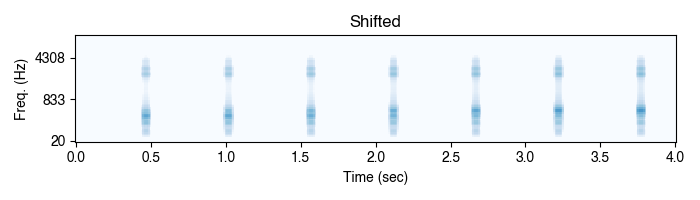

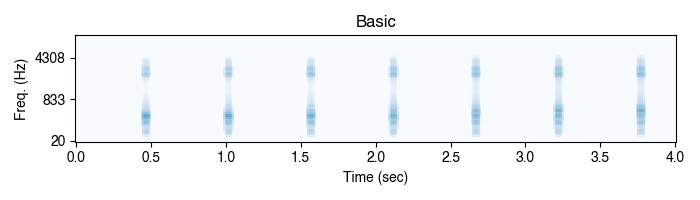

A basic continuum of seven stimuli was constructed by shifting the first spectral peak ("formant") of a 125 Hz harmonic tone from 375 Hz to 500 Hz. This continuum was perceived as shifting from /I/ to /e/ (Figure 6E, first row).

A new shifted continuum was then constructed by adding a 500 Hz pure tone overlapping with each harmonic tone of the basic continuum (Figure 6E, second row). Because the formant is higher, this continuum starts sounding like /e/ earlier in the sequence (causing a lower threshold).

Last, the early-onset continua were constructed (Figure 6E, third row). The harmonic complex in these continua are physically identically to those in the shifted continuum. The only difference is that the added tone begins earlier.

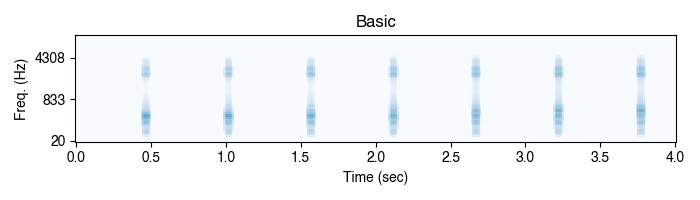

To more easily see these changes, click on the next image to cycle between these three sequences. Notice (1) how the formants shift upwards from basic to shifted, and (2) how the vowels remain identical between shifted and early onset.

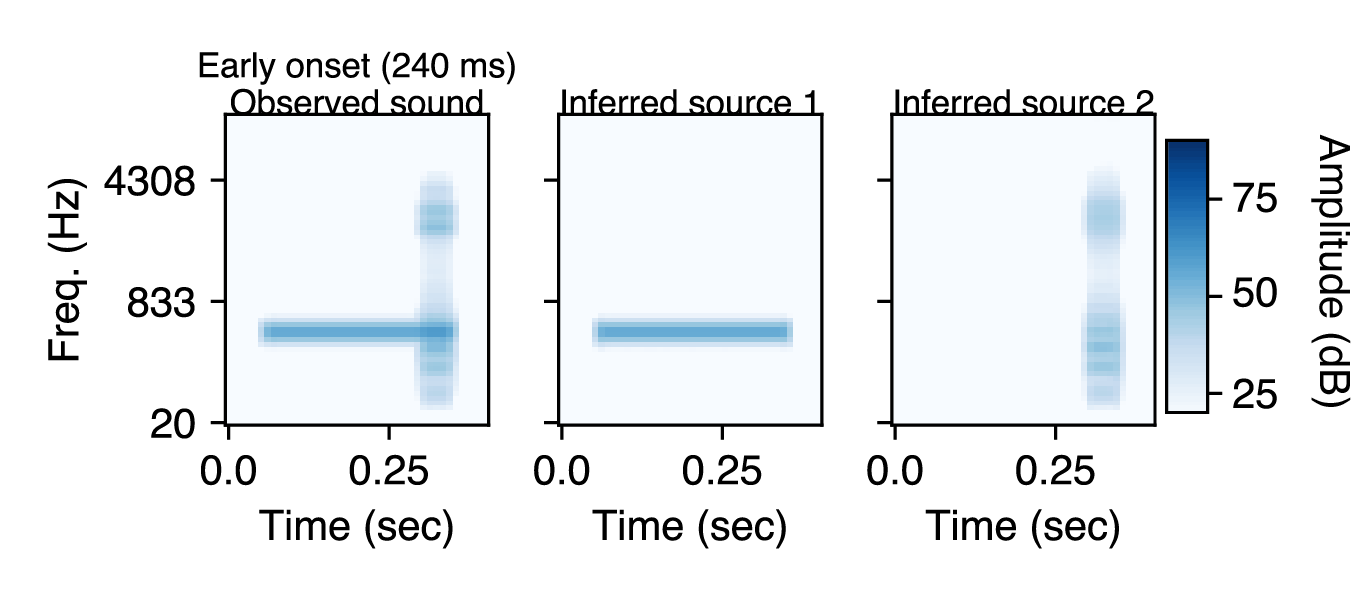

Despite their physical differences, listeners perceived the early-onset continua to have a similar vowel boundary as the basic continuum (Figure 6F). These results indicated that the pure tone was not integrated with the harmonic tone when their onsets differed.

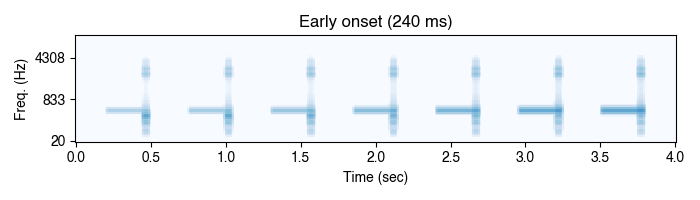

Finally, the following is a model inference (using sequential inference). The stimulus is the second last in the early onset sequence. Notice that the vowel looks more like the corresponding one in the basic rather than the shifted sequence.

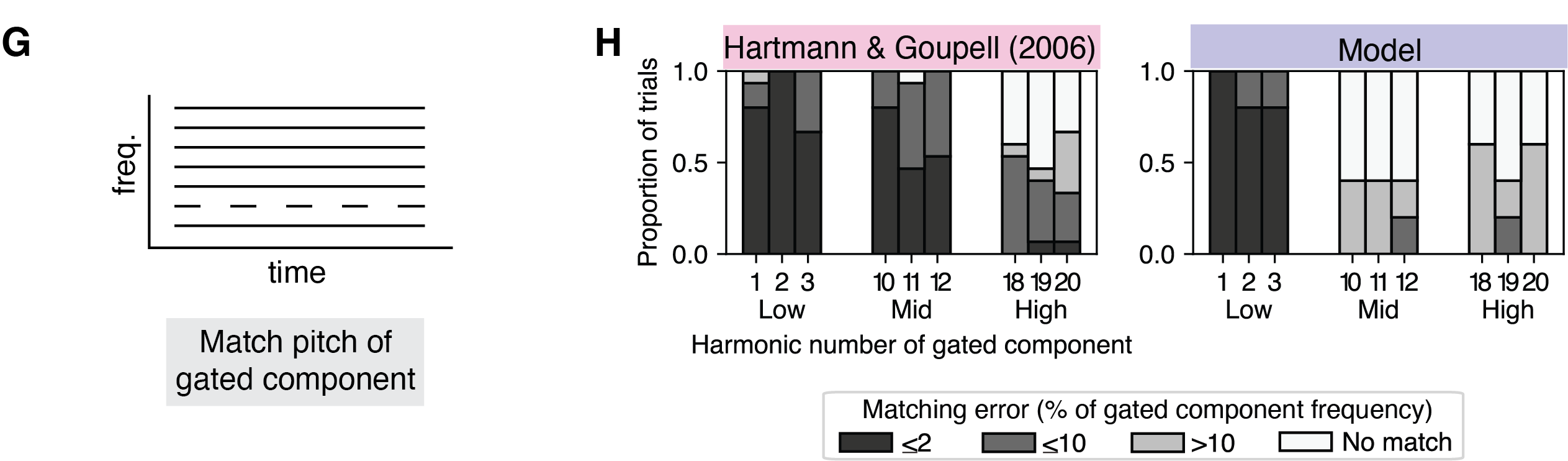

Cancelled harmonics (Houtsma et al., 1988; Hartmann & Goupell, 2006)

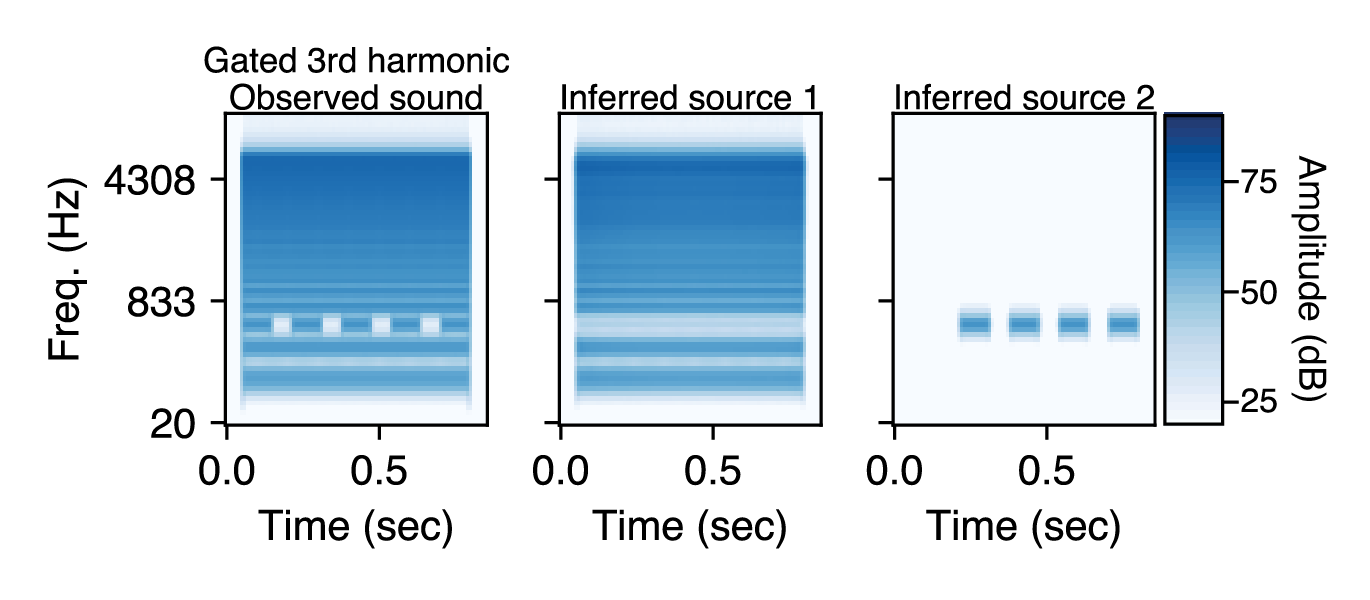

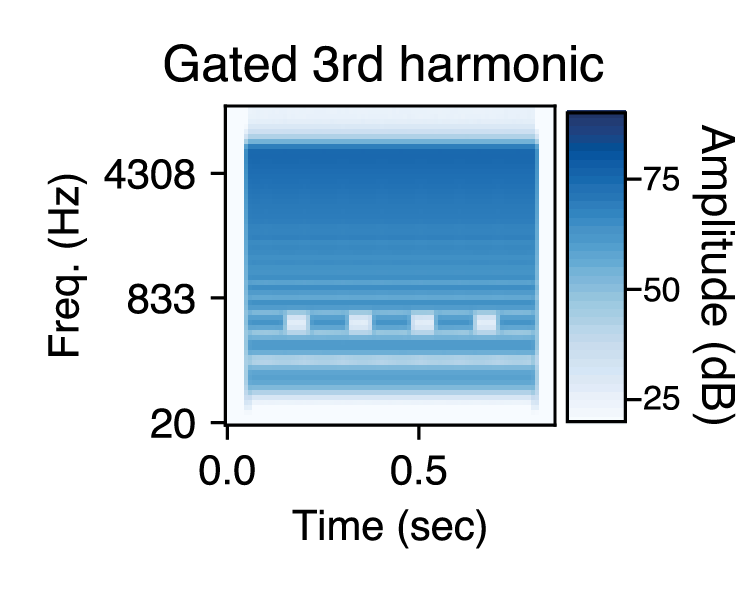

The "cancelled harmonics" stimulus (Houtsma, et al., 1988) provides another example of cue conflict: for the duration of a harmonic tone, one of its components is gated off and on over time. Although this gated component remains harmonically related to the rest of the tone at all times, it perceptually stands out as a separate component. Here is an example experimental stimulus, with the third harmonic gated.

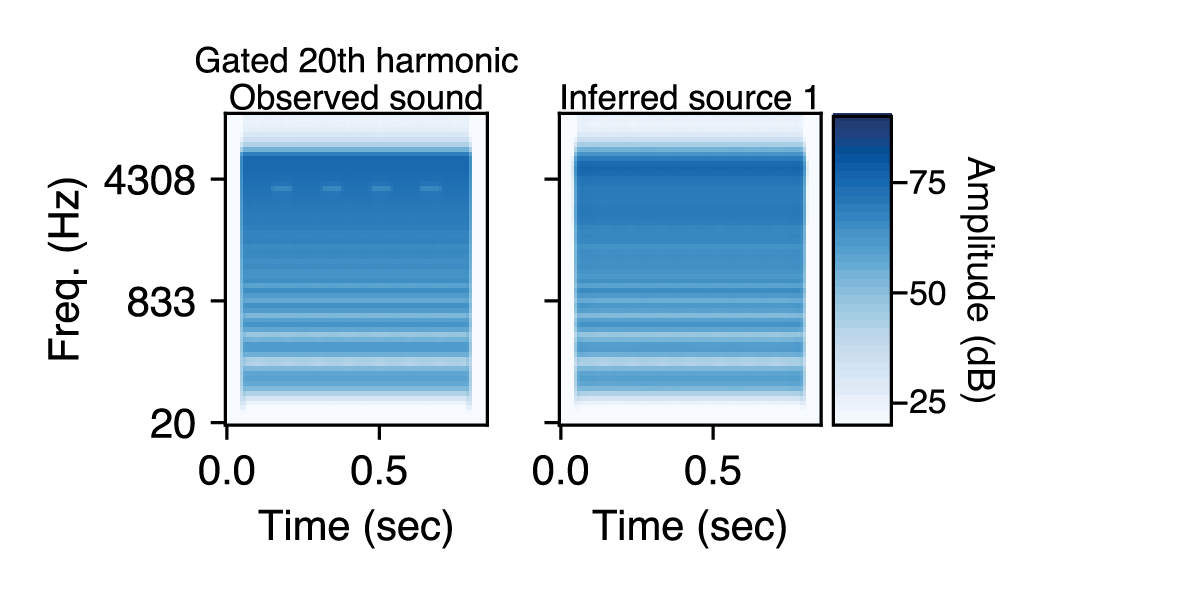

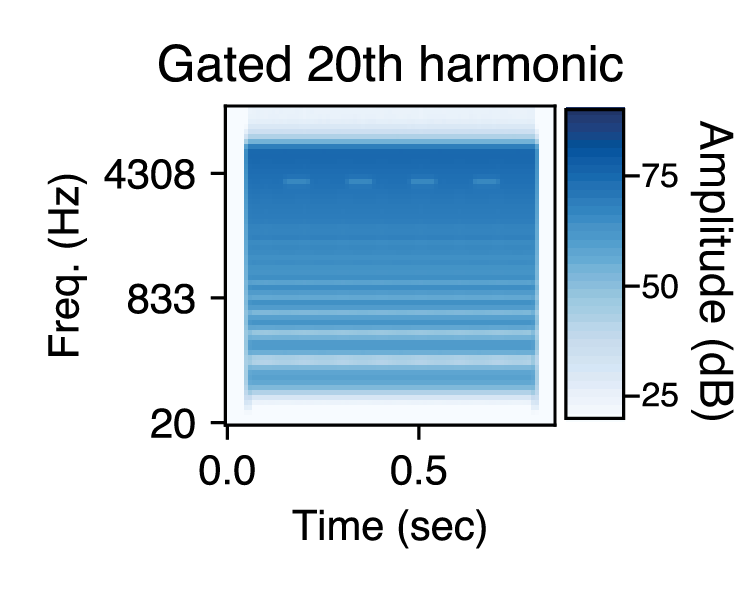

Hartmann & Goupell (2006) used a pitch-masking task to investigate cancelled harmonics. They found humans were worse at judging the pitch of the gated harmonic at high harmonic numbers. Here is an example experimental stimulus, with the twentieth harmonic gated. Notice that this harmonic is more difficult to hear.

Finally, the following are examples of model inferences (using sequential inference).